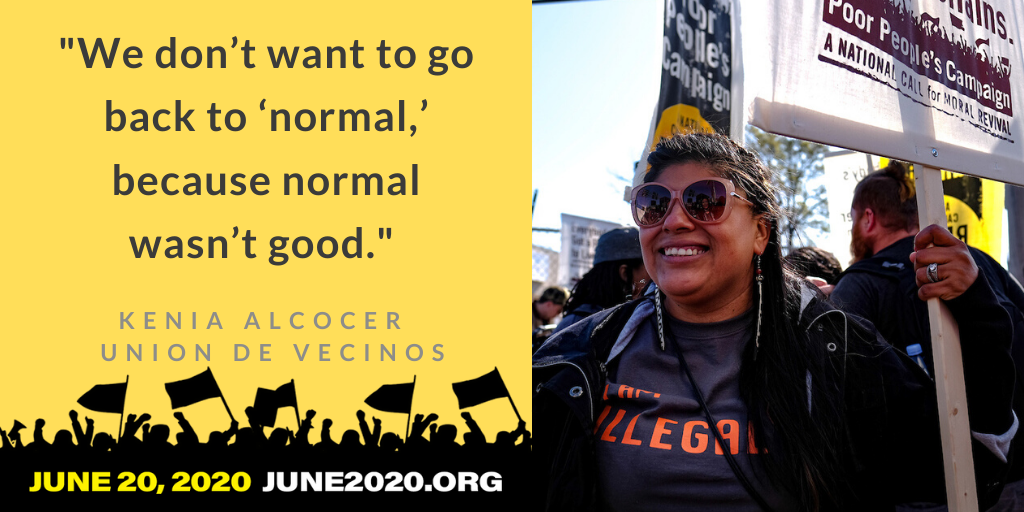

Kenia Alcocer, Co-Chair of the California Poor People’s Campaign, Organizer with Unión de Vecinos, Eastside Local of the Los Angeles Tenants Union

Immigrating to Los Angeles as a small child, soon witnessing the 92’ riots after the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, and later navigating access to higher education as an undocumented person, have been some of the forces that have shaped Kenia Alcocer’s life and work. As a teenager she became involved in the Unión de Vecinos, Eastside Local of the Los Angeles Tenants Union, starting to organize to prevent the eviction of her aunts from their homes in the projects of Boyle Heights. Kenia then came on as a full-time organizer, supporting the formation of neighborhood committees in Boyle Heights and the City of Maywood, and driving campaigns for clean water and safe housing. Kenia is currently the Co-Chair of the California Poor People’s Campaign.

I grew up in Watts, we got here from Mexico in late 89, when I was 3 years old. The 92 Watts riots were my first impression of how things really were in this country.

Systemic racism is very much felt in that community, especially when the cops try to play the Latino vs. Black card against community members. I understood from a young age that the system has people fighting over resources.

I wasn’t the typical undocumented young person that came here and didn’t know I was undocumented. I was really young when I arrived, so that could have been a possibility but my parents decided to tell us that we were undocumented and how we needed to study and pursue things differently. When I was in high school I started getting politically involved. I knew that college wasn’t a possibility for me because of my status so I got involved in a campaign to pass state legislation that would allow undocumented people to pay in-state tuition at the universities.

When I graduated in 2003 the bill had been implemented so I was in the first year of undocumented students that got to go to school and pay in-state tuition.

I started getting involved in housing issues when my aunts were in the process of being evicted and were fighting for their homes in the projects in Boyle Heights. They were founding members of Unión de Vecinos. I fell in love with the work and stopped going to school for a while to really commit to the organizing I was doing in the neighborhood.

Boyle Heights is a very vibrant, low-income community. People walk a lot here even though there is hardly any green space. You see a lot of street vendors, and if you go to Plaza del Mariachi you’ll see men wearing mariachi suits on the corner asking folks to be hired. It is also a community that’s been heavily under attack since the 90’s through a gentrification process.

This has been an immigrant community for a long time. Now it is mostly Latino but back in the day we used to have a lot of Japanese community here. During World War II they were ripped out of their homes and sent to internment camps so that community was completely removed and displaced. Displacement is very typical in Boyle Heights. It’s something that’s been dealt with before and something we continue to fight against.

Before this pandemic even started we were organizing to get rent control at the state level, we were organizing to get eviction moratoriums, we were organizing to get anti-harassment laws for tenants. We don’t want to go back to ‘normal’ because normal wasn’t good. Going back to ‘normal’ means going back to people still dying, going back to people still being homeless, going back to people not having access to healthcare.

On April 1, we decided to go on rent strike because a lot of our members said they didn’t have the money to pay. We are also telling people who are still working, like myself, to not pay rent. Why? Because you don’t know every time you step your foot outside the door, if you’re gonna get sick or not, you don’t know if you’re gonna bring that disease back to your family. Keep that money to feed yourself, keep that money to buy your medications, keep that money to stay alive. Choose life over death. That is a basic principle of the Food Not Rent campaign.

If our work is essential then you better provide for our essential needs — we need housing, we need healthcare and we need better working conditions and better pay.

We’re also encouraging folks to stay at home, stay alive, let’s show this country that we’re not just essential as workers. If our work is essential then you better provide for our essential needs — we need housing, we need healthcare and we need better working conditions and better pay.

During this pandemic, we are being shown that things we were told were impossible are actually possible. So we are using this moment to open people’s eyes to the possibility of things really changing and for us to push for something that is bigger and better.

But to do that we need to keep protesting and showing the racist structures of this system — because when it comes to folks that are organizing outside, our folks are the ones being criminalized even while wearing masks and social distancing, while the folks with guns and no protective gear taking over capitol buildings are not. They are getting more respect from law enforcement than we are!

People are coming together, people are organizing, people are mobilizing. We are part of the Poor People’s Campaign because it is being led by the poor who are doing the groundwork across the country and leading this campaign to where it needs to go. Poor people know what their suffering is and poor people know what the cure is for that suffering, and the Poor People’s Campaign has given us the tools to really build the power that is needed to make sure that we create a tremendous shift and revolution in this country.