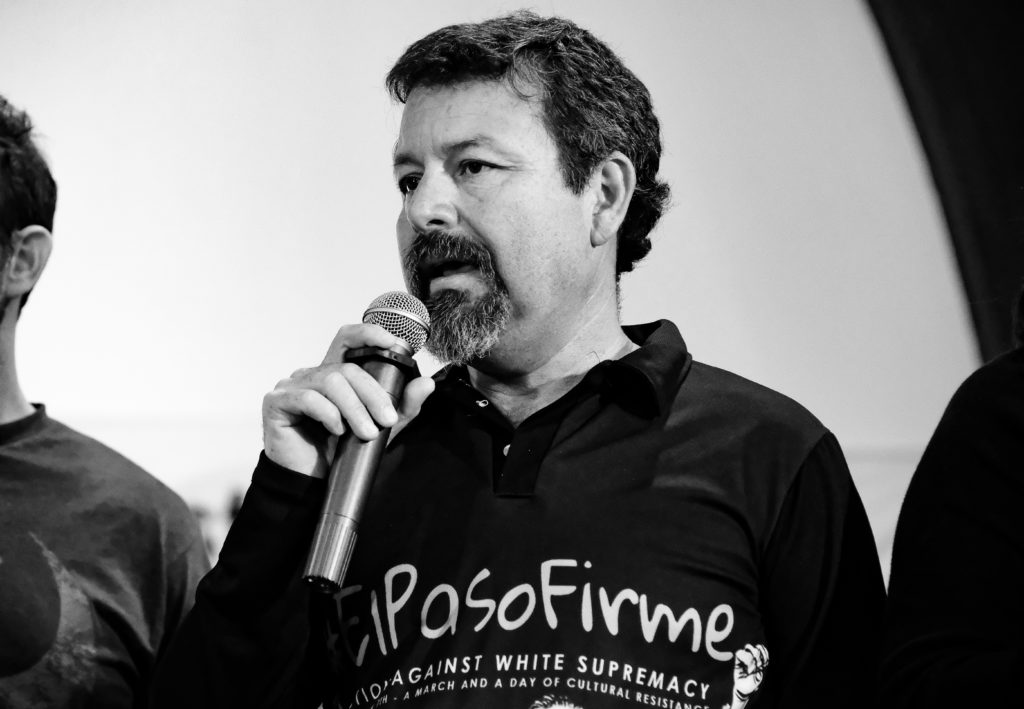

Fernando Garcia, Border Network for Human Rights

Fernando Garcia, is the co-founder and director of the Border Network for Human Rights, a partner organization of the Poor People’s Campaign based in El Paso. The BNHR organizes with border-impact communities in West Texas and Southern New Mexico as part of a broad movement for human rights. Learn more: https://bnhr.org/

The border is not just a piece of land in the middle of the desert with no people. We have vibrant, proud communities where we live at the border. El Paso and Juarez collectively make up the largest metropolitan area with close to 2.5 million people.

This is a bi-national community. When I say bi-national it’s not because you cross from one side to the other side or because some people speak Spanish or English or are bilingual. It’s binational because these communities are interdependent. You cannot understand Juarez without El Paso. Not only in terms of economic relations but also family relations, social relations.

We have a lot of poverty here, especially in new immigrant communities, in what we call colonias. Many people would know them as suburbs, but in this case, instead of being where rich anglo people live, it is where poor new immigrant communities live in trailers. If you were to visit them, you would say, ‘Well, this is not America. There’s no running water. There’s no pavement. There’s no electricity.’ Well, this is America, and this is poverty. We have thousands of people living in those conditions.

On top of that, this is a community that is being militarized. And when I say militarized, I’m taking this very seriously. We have what is supposed to be a police force acting as a military force, which is the Border Patrol. They consider themselves a paramilitary unit, not a civilian police force. In their mentality, there’s an enemy out there, there’s a war out there. That is the narrative that they have produced in the minds of these agents.

When you ask who the enemy is that these militarized institutions are fighting, you look around and realize that this is not about drugs because then they, the institutions, have lost that war, and it’s not even about terrorism because there hasn’t been a single case of terrorism or terrorists being arrested at this border. So if it’s not about drugs or terrorism, then what is this war about?

You come to the conclusion that this is a war against poor people, against immigrants. For that war they have not only built walls, they are using war technology like drones, sound detection systems, night vision, vision towers. The drones they use are the same ones that carried missiles in Afghanistan. They are flying overhead. You will also see the deployment of the National Guard, and recently, with Trump, the deployment of active duty soldiers.

I don’t like talking about myself much, because I think whatever we have accomplished here in El Paso has been the result of a collective process, but I grew up in Mexico and was part of the student movement there when I was in high school and then in college. At that time, in the 80s, the movement centered around school fees – they were too high for people to have access to the university. We built a movement to lower the fees for college, and that was how I became connected with what later became, for me, a broader struggle for justice, rights and social change.

I studied journalism as well as Mexican archeology, but mostly journalism. I started working in several newspapers in several states in Mexico, and then in the late 80s/early 90s ended up in Ciudad Juarez, the border city with El Paso, working at a newspaper there, as well as a political magazine. That’s where I came into contact with the other side of immigration, one that I wasn’t aware of.

In the 60s, my family migrated to California. My granddad was part of the Bracero program, so he was going back and forth working as a guest worker in the fifties and sixties, but then my whole family started moving little by little in the sixties and seventies.

So in the end, I realized that most of my family were in the United States already, even my mother and my father. At some point they moved to Los Angeles. But at that time they flew in airplanes and they used passports, very different from what we see now happening in the southern border of the US now.

What I discovered when I came to Juarez is that not everybody had a passport. Not everybody will just take a plane and go to Los Angeles and be there. There were many more people, poor people, coming from countries like Mexico, but also Central America, who couldn’t afford all of that, and they didn’t have any documents. They didn’t have passports or visas, they were just crossing the border away from the ports of entry, the places where one would officially enter the country, like an airport or border checkpoint.

When they crossed, they faced not only the uncertainty of being undocumented, the uncertainty of looking for a better life in United States, but a very aggressive racist culture of abuse spearheaded by law enforcement, especially by Border Patrol, la migra, we call it.

I started to really get in contact with these issues of law enforcement abuse, of shootings, beatings and even rapes, so I decided to move to the United States. Fortunately, I was able to get a visa and then residency through my family relations. Once I came to the U.S. in the 90s I started to travel to different areas of the country where most immigrants were concentrated at that time.

So I used to live in Phoenix, Arizona, in Houston, at some point I spent time in Philadelphia, I visited Chicago, New York, Los Angeles. I started really traveling and knowing the reality of immigrant families here. And I realized that they were not only suffering abuse, but even though they were already part of the society, working hard, paying taxes, even creating families, and actually opening businesses, basically establishing themselves in the United States, all of them were essentially invisible. They did not exist for the rest of society.

The immigrants were needed in the construction business, to build roads, to pick the food, to take care of the sick, to clean houses – they were needed by the economy, but they were not recognized. Not only in terms of work, but they were not even recognized as human beings. And in a way, to do that, not to recognize them, to call them illegal aliens…what is that? I mean, when I think about illegal aliens, I’m thinking about somebody from outer space, somebody that is not a human being.

So that realization had a deep impact on my framework. When I came back to El Paso in ‘98 I came back with a firm commitment to making our communities visible. And the only way to do that was to build an organization that was led by immigrants, that was framed by immigrants, and that was composed of families expressing their voices, and using the human rights framework. Why human rights and not immigrant rights?

Because the situation of many immigrant families, workers, children, mothers, fathers, in terms of housing, healthcare, education, everything aside from legal status, the economic and political situation of Latino immigrant communities is the same as other communities in the United States. Black, African American, Asian, Indigenous…We are all under one system of oppression, of exclusion, of criminalization, of militarization.

We are all under one system of oppression, of exclusion, of criminalization, of militarization.

So there’s no such thing as rights for immigrants and there’s no such a thing as rights for specific sectors or groups – there are human rights for every community – the right to be recognized, the right to have dignified work, housing, culture, education, all of that ought to be the same for every community. All communities should be equal in dignity and rights.. For me it was very important that the organization would not only be composed by impacted communities but would also have that framework.

The Border Network for Human Rights was one of the organizations that inaugurated the first coordinating committee of the contemporary Poor People’s Campaign, at the Highlander Center in Tennessee. The original Poor People’s Campaign in 68’ was convened by Martin Luther King Jr. and others, and it brought together people from all different poor communities – Cesar Chavez was there, Indigenous people were there, some white progressive people were there. They realized that the fight against poverty and for a better society didn’t belong to just one community. It wasn’t called the immigrant people’s campaign or the Black people’s campaign. He called it the Poor People’s Campaign because we are fighting a common enemy, a common system of oppression.

The issues happening with border communities are happening in communities in the rest of the nation. Accountability for Border Patrol, demilitarizing the border, decriminalizing immigrants, immigration reform – these are not isolated systems or solutions that would only impact immigrant families, these are part of interconnected systems within the United States that impact multiple communities. The brutality of Border Patrol or local police against immigrants is the same brutality that is being suffered by other communities in the nation. The militarization of the border is not different from the militarization of local police departments. Immigrant families are some of the poorest in the country, but there are other poor communities as well.

We need to understand that the system impacts all of us, and so the solution has to come from all of us. Immigration reform and demilitarization of the border and all of that will never happen if it’s not connected to a larger human rights movement in the United States.

We need to understand that the system impacts all of us, and so the solution has to come from all of us. Immigration reform and demilitarization of the border and all of that will never happen if it’s not connected to a larger human rights movement in the United States. The Border Network for Human Rights had that clarity from the very beginning because we knew that the struggle of immigrants wasn’t only for immigrants, it is for every human being in this country, in this world, to be equal in dignity and rights. We were just looking for the right vehicle.

We had tried other vehicles in the past, other campaigns, but when we became part of the Poor People’s Campaign it was very clear for us that this was the vehicle that was gonna take us there. That was not only gonna connect our struggles, but was going to add to our struggles. It was a way of digesting the idea that we are all together, fighting all of these systems, and if we don’t do it together we’re gonna fail. So that is the goal, the challenge, and the risk with the Campaign, and why we connected with it.

In 2000 we started an unprecedented engagement process of holding Border Patrol accountable. What we have done almost yearly since then is to try to document the stories of abuse. This documentation campaign is now done by members of our community. Each year we train hundreds of documenters in our community, so they ask their own neighbors and friends and families if they’ve had an experience of law enforcement abuse, and collect the cases.

The idea of the documentation has become an important tool for people to tell the stories of abuse, because if we don’t say it, it doesn’t exist. It can be cathartic to say it, when your dignity and rights have been violated by Border Patrol or the police. They may enter your home, scare your children, insult you, beat you, sometimes they even kill you – so this gives people a platform to speak about the abuse.

But the second thing that is important for us is that our documentation campaigns allow us to get in contact with impacted communities and community members and invite them to be part of an organized process. We’re not gonna offer a solution for individual cases because it wouldn’t resolve systemic abuses. Of course, sometimes we talk to attorneys to do litigation in some specific extreme cases, but most attorneys won’t take more routine cases like “They just called me wetback.” or “they just told me that I don’t belong here,” or “they just pushed me, and they scared my children.” Those cases are very common and most attorneys won’t take them.

So we invite those people to become part of the Border Network. Because collectively, through organizing, we can push for change. And we have forced the Border Patrol to sit down with the community and explain themselves, explain their policies, their practices.

By 2010, ten years after we started the documentation campaigns, and in addition to intense organizing work, including community forums with Border Patrol and the police, the number of abuse cases we saw coming from Border Patrol dropped to 30%. By 2015 it was less than 10%.

So through organizing, and when I say organizing I mean families coming together permanently and increasing the members in the human rights committees that we have, and getting trained as human rights promoters, we have actually been able to create this local accountability process. Of course the cases of abuse were still ongoing, but at least we had a process for engaging these agencies.

We have some committees that have been meeting for years already. People, families come, they stay. Most of them stay, some of them are new. Some of them go because they need to move from one community to the other. But every week now they are meeting as if they’re going to church. They are meeting to discuss the problems, their issues, to learn more about the struggle and the reality, but also to provide the solutions. The Border Network right now has 40 human rights committees that integrate close to a little less than 1000 families because our membership is a community of families. So that is the force behind the organizing structure. It’s a permanent organizing structure that is not up to the whims of any particular campaign. Whatever issue they feel that they need to tackle is the priority.

The last four years, under Trump, have really threatened this engagement model with law enforcement. During this terrible Covid-19 pandemic, the Trump administration has implemented a new rule called Title 42 which allows them to expel people from the country without any due process. They also changed Border Patrol leadership locally. They brought in this guy that was more like a military type of Border Patrol chief, the one that actually put children in cages in the past. El Paso was the place where the children in cages happened. El Paso was where the rejection of refugees happened at the ports of entry. El Paso was where they put the makeshift detention camp by the Rio Grande river. We saw a major increase in abuse. So we fought every fight, and we fought hard.

And then the shooting at Walmart happened. This was a planned and intentional attack. This guy came from Northern Texas to El Paso because El Paso has become not only the epicenter of the anti-immigrant agenda, Trump, but also the epicenter of the resistance. So they wanted to crack that resistance. That’s why Walmart happened.

El Paso has become not only the epicenter of the anti-immigrant agenda, Trump, but also the epicenter of the resistance.

After that attack, we forced them to change the Border Patrol chief and they replaced him with a Spanish speaking Latina woman, who in just the last year has met with us more than 10 times and participated in five community forums. So I do believe that even in the worst scenarios, the organizing and the resistance of the communities is what makes the difference. That doesn’t mean that these cases of abuse are not still happening. What we’re saying is that our aim is to make this law enforcement accountable to people, to communities, to human rights and to the Constitution.

We never thought that we would be organizing in the middle of a militarized zone. But we did. We’re resisting. We’re challenging ourselves, and we’re challenging society. Saying yes, we can organize. And yes, we can bring people together. And yes, we can change. So that is what I’m proud of. El Paso is one of the safest cities in the United States, not because of law enforcement but because of its people. And I do believe that if we can organize a human rights project in El Paso, at the border, we can organize it anywhere.

I passionately believe that throughout this experiment called America, immigrants and borders have defined the character of the nation. We are a nation built on the backs of poor and exploited immigrants, from the extreme horror of slavery, to the poor European immigrants working in factories with no labor rights, from the exploited labor of the Chinese building the railroad to the Mexican bracero program. Exploited yes, but we also resisted in every instance, and forced this society to recognize our contributions, legacies and rights.

I believe that the character of the Nation for the 21st Century will be defined in regards to our approach to immigrants, and what happens at the US/Mexico border in particular. Will we be a Nation that puts migrant children in jails and builds a border wall as a shameful symbol of hate, white supremacy and xenophobia, or will the US-Mexico border become the New Ellis Island, where immigrants are seen an intrinsic part of the future society, one more diverse, multicolored and fair?